Six Principles of Convivencia

Friction between uses and users is inevitable if we are committed to public space. Convivencia is a capability to coexist across differences. This is how public space organizations can approach it.

Over the next few months, I will be doing several workshops and keynotes on the idea of convivencia, a subject I have been working on for several years first as a leader, then as a researcher and now as a consultant.

Public organizations, like libraries, museums and parks, are searching ways to turn the unpredictability, inequality, and complexity of urban life into thriving places, equitable services, shared experiences, and great places to work. Creating and holding space that is welcoming and inspiring for everyone is easier said than done in a world of increasing complexity and diversity, vitriolic public debates, and existential societal, social and ecological challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic multiplied the real and perceived risks in coming together and sharing assets with strangers. It disrupted most convening practices and pushed millions of people into social isolation, illness or poverty.

Convivencia is a Spanish term describing the capability to co-exist and create pragmatic solutions across differences. The goal in convivencia is not to erase differences or solve them. Convivencia is about being at ease with differences and navigating them in a manner that builds confidence in public life and institutions. It is finding the right balance between harmony and conflict for each context. Achieving convivencia requires will and capabilities from institutions and individuals. My message both in my talks and consulting is:

I am not here to tell you that if you do these six things, all your problems will go away. What I want to say is that if we understand the reasons behind friction and invest in skills and confidence to navigate it, we can create public spaces that are inviting, inspiring and equitable places to visit and work. I am not claiming that friction is easy. It is often frustrating, scary, uncomfortable and even harmful. But it can also be joyful, creative and playful. If we feel confident, capable and inspired, we can be at ease with the unpredictability of public life.

Based on my engagements with hundreds of public space organizations and diving into theory from theology to philosophy, I have developed six main principles of convivencia. There are written specifically for public space organizations.

My understanding of convivencia challenges naive, let´s-just-all-get-along approaches to togetherness. I believe convivencia allows organizations to set achievable expectations and frame certain levels of friction as a sign of success. I suggest a set of convivencia skills that public space organizations can invest in. I emphasize the role of experiences of belonging, joy and wonder to balance the often frustrating or intimidating parts of coexistence. I argue that public space organizations cannot be successful in convivencia without partnerships. All and all, I believe that fostering convivencia frames public space organizations as critical learning grounds for liberal democracy.

What is Convivencia?

The rapid growth of cities as a result of industrialization and migration from the 19th century onward escalated the need to seek ways to share crowded spaces with strangers. An indifference to difference or blasé attitude emerged in 19th century Europe and North America as a coping mechanism. Letting others be and being left alone created a protective shield and enabled autonomy. These urban social strategies have been described as coolness and rationality (Sennett 2012), blasé (Boy 2021), civility (Sennett 2012), “simply letting be” (Barker et al. 2019), sprezzatura (Sennett 2021), friendly distance (Redshaw & Ingham 2018), or indifference to difference (Barker at al 2019).

From the 1970s onwards, initiated by Ivan Illich’s book Tools for Conviviality (1974), a growing field of research has evolved around the notion of conviviality, understood as our ability to live with others across differences. Tony Addy (2023) writes eloquently on conviviality in a publication for the Lutheran World Federation:

Convivial life together implies working on the borders between people, whether they be political borders or cultural and religious borders, or borders connected to personal identity.

Conviviality, understood as the capability to coexist (Wise & Noble 2016) is something that can be felt as a welcoming and creative atmosphere. At the same time, it is slippery and difficult to predict and manage. (Barker et al., 2019) This essay is an attempt to define the role public space organizations can play in creating conditions for it (Wise & Noble, 2016).

Researchers and practitioners vary on whether they talk about conviviality, convivialism, or convivencia. I use the Spanish term convivencia instead the English word conviviality for two reasons. First, in colloquial use conviviality is often associated with ideals of happy togetherness (Addy, 2023; Wise & Noble, 2016). Second, the Spanish phrase comes with an emphasis on joy while recognizing that when we share space and resources with those who are different from us, there is bound to be a need for negotiation and adjustment (Wise & Noble 2016; Ocampo, 2024). Third, convivencia is a phrase commonly used in Spanish to describe urban policy interventions and sociality in a way that does not have a direct translation in English (Blattman et al, 2022; Ciudad Buenos Aires, 2020; Ocampo, 2024; Páramo et al. 2023; Páramo 2013, Páramo et al. 2019; Wise & Noble 2016).

Six Principles of Convivencia for Public Space Organizations

My research and consultancy has focused on looking at convivencia in the context of public space organizations, like libraries, museums, and parks, and seeking practical application. I summarize my approach in six principles:

Principle 1: Convivencia requires both will and skills to recognize and navigate friction.

Living together across differences is like going to the gym. We become better at dealing with differences when we practice regularly. The “convivencia muscle” is something people can build in public spaces. Approaching living together as learning skills allows public space organizations to position themselves as vital institutions for the future of democracy while connecting to their legacy as learning institutions.

When public space organizations think about ways to be learning grounds for convivencia, this work can be informed by looking at the strategies of belonging, solidarity, and resistance that marginalized and stigmatized minorities use to navigate environments that are stacked against them. In an ethnographic study on migrant youth in London, Les Back and Shamser Sinha (2016) identify five convivial skills that migrant youth demonstrate to “make space to live within a city that remains divided by racism” (Back & Sinha 2016). These are:

fostering attentiveness and curiosity

care for the city and a capacity to put yourself in another’s place

worldliness and making connections beyond local confines

develop an aversion to the pleasures of hating

make connections and build a home.

Using libraries as an example, these are skills that people can learn by spending time at the library, utilizing its collections or participating in its programs.

Principle 2: Convivencia requires partnerships.

Public institutions, like libraries, cannot be successful in convivencia without partnerships. At the same time, it is important to note that partnerships can also pose risks for institutional legitimacy. Without a commitment to good governance, equity and friction, partnerships can promote paternalistic, top-down solutions and expand existing inequalities (Greenspan and Mason 2017; Foster 2013; Saunders-Hastings 2022). Convivencia provides a language to reap the benefits of partnerships while mitigating their risks.

In the research project I led at the Bloomberg Center for Public Innovation at Johns Hopkins University, we identified four partnership capabilities based on case studies of public space partnerships in Amsterdam (The Netherlands), Fortaleza (Brazil), Mecklenburg County (The United States), Philadelphia (The United States), and Los Angeles (The United States). The four capabilities, which we will describe in greater detail in upcoming publications, are:

navigation

convening

experimentation

codification

Principle 3: The goal in convivencia is not to dissolve differences.

Convivencia diverts from many other approaches to public policy and innovation because its focus is not on problem solving. Convivencia does not strive to solve differences but build on them. It takes differences as given. Convivencia is a commitment to live with those with different customs, needs and world views without trying to change or dominate them (Addy 2023; Glitzenhirn, 2014). It requires being at ease with differences without a fear that the exposure to other ideas and beliefs would jeopardize one’s own conviction (Addy 2023; Glitzenhirn, 2014). The idea of sitting comfortably in differences without the goal of conversion is central to convivencia. It might be that the engagement with different partners results in changes in one’s way of thinking but that is not the goal in convivencia. Convivencia is seeking opportunities where our interests and needs align sufficiently for shared action.

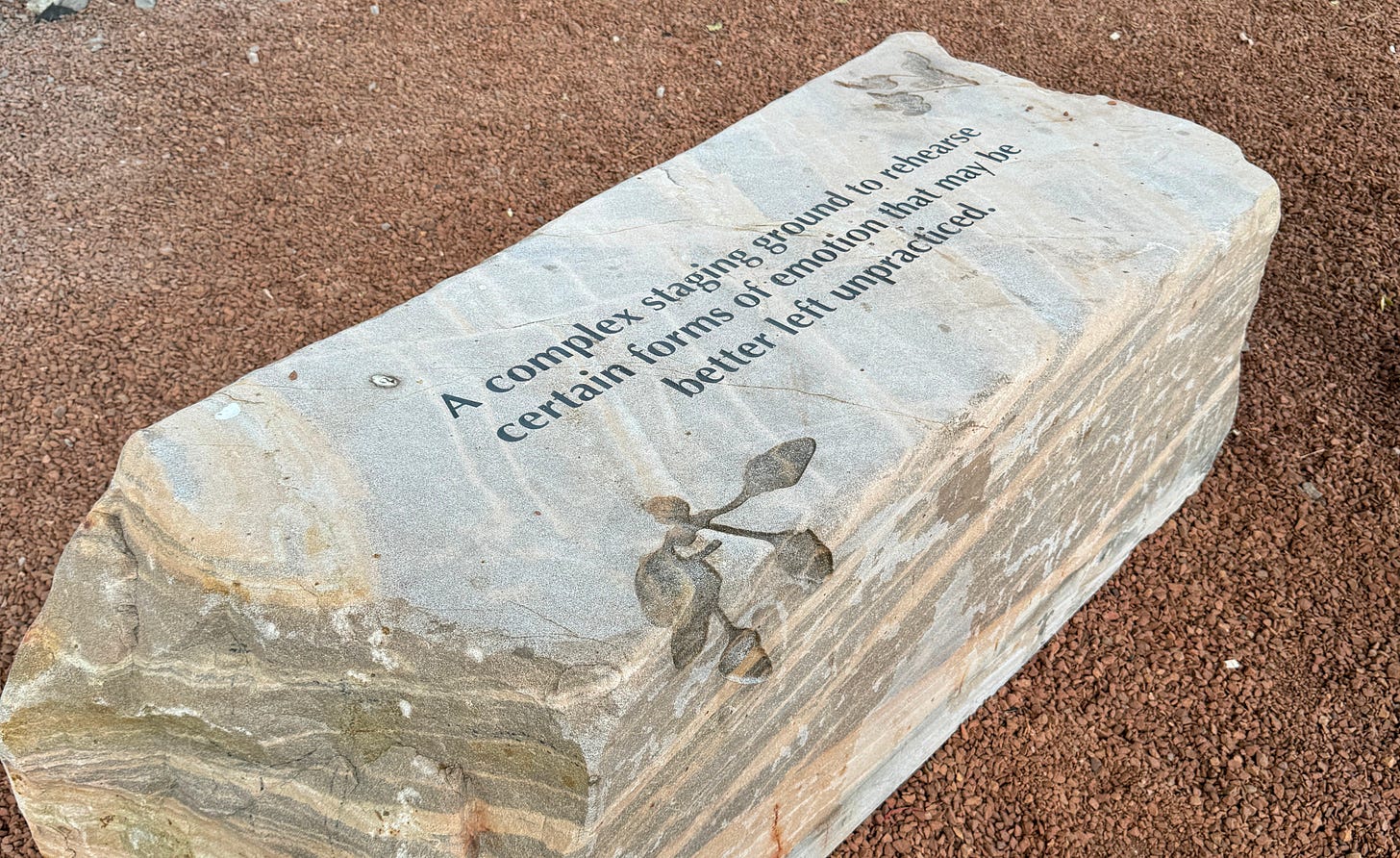

Principle 4: Convivencia is a creative space between harmony and open conflict.

I describe convivencia as the space between harmony and open conflict. As an illustration of this space, Spanish philologist Américo Castro has used the term ‘la convivencia’ to describe an era in Spanish history (approximately 700-1492) when Judaism, Christianity and Islam were aware of each other, shared physical territory (Spain) but were not in violent conflict. Castro and others depart from a naive idea of conviviality as happy togetherness and note how this era was not without friction, prejudice and competition. But most critically, this nonviolent coexistence of different belief systems resulted in progress in science and the arts (Mann, V. et al., 1992).

Convivencia contributes to creativity when all parties can learn from diverse perspectives and are able to expose their ideas to diverging viewpoints. The presence of friction is critical for discovery, learning and imagination.

I am doing a lot of my work with libraries. For library staff and library organizations this recognition results in a balancing act between harmony and open conflict. At times institutions and their staff have to defend the right of some people or some communities to join public life, i.e. expose and encourage friction to ensure equity. At other times their role is to find ways to de-escalate a conflict to ensure a safe and welcoming environment for everyone.

Principle 5: We need experiences of wonder, play and belonging to commit to convivencia.

A serious commitment to convivencia requires an acknowledgment that coexistence is not always fun. Therefore, for us to commit to do the often difficult and at times frustrating work of coexistence and negotiation and join public life with all its messiness, risks and wonder, public spaces need to provide something that makes tolerating that worthwhile.

Public spaces, like libraries and parks, need to provide something that we cannot obtain or experience in private or commercial spaces and cannot experience completely isolated from other people. They need to provide us with awe, wonder, joy and play. They need to provide experiences that elevate us and allow us to see the common humanity between highly different people and users while illustrating our differences. This is something that the humanities and the arts can do better than anything known to man. But in the same spirit, these spaces can provide access to nature or technology in a way your backyard or your living room never can.

Public space institutions need to do a better job in making the connection between investments in experience, awe and wonder and the future of liberal democracy. Simultaneously, they need to ensure that they provide opportunities for wonder, play and belonging also to their staff.

Principle 6: Convivencia has two levels: the democratic level to coexist with strangers and the affinity level to take action, convene and care.

I suggest looking at the interpersonal relationships in public spaces on two levels: between all users and between affinity groups.

Democratic Level: On the outer level, as a promise for everyone, the goal is to create conditions for getting along while recognizing that there is bound to be friction and need for negotiation.

Affinity Level: On the inner level, public spaces can provide guidance on how public spaces can sustain, support or build communities of interest. Here the goal is creating opportunities to do things together with others while recognizing that we all do not want to do the same thing.

While the outer level is grounded in diversity, human rights and democracy, the inner level builds on commonality, affinity, shared interest, care, and even love. Providing the democratic level, the ability for everyone to coexist and carry out one’s own endeavors without risk of violence or discrimination or a pressure to conform, is a fundamental value in cities.

Acknowledging friction and building reasonable expectations around coexistence needs to be coupled with a recognition that mere contact or proximity does not automatically lead to a flourishing democracy, mutual understanding and acceptance. The democratic level does not emerge just by opening doors and letting people in. Actually, contact and proximity can and does often reinforce or create prejudice and stereotypes (Powers et al., 2020). Therefore, fostering convivencia requires intentional action and professional capabilities, like representation of diversity in spatial design and staff, inclusive customer engagement and diverse programming.

It is important to note that putting more focus on getting along does not mean that libraries, parks, libraries and cultural centers would or should not strive for social interaction and a sense of belonging. Quite the opposite. Non-hostile coexistence, the democratic level, is a prerequisite for the affinity level. Shared activities are fundamental for building confidence in public life and democracy as a whole (Neal et al. 2019) and important ways to tackle social isolation and loneliness. Programming, staff behavior and public spaces in general can bring people together around shared interests and support existing communities. A sense of belonging created through shared activities and friendships is fundamental for individual wellbeing.

This two-leveled thinking about public spaces highlights one of the essential differences between public and private organizations. While people always have the right to opt out of engagement or decide not to attend a program, public institutions do not have the right to give up or opt out from some audiences. A serious commitment to convivencia requires attentiveness on which communities are using the space now. It requires creating incentives and removing obstacles. Public space organizations have a responsibility to constantly create better ways of reaching out while understanding that everyone does not need to use the space for the same reasons, at the same time or in interaction with others. While public space organizations can set priorities, do targeted programming and channel more resources to some communities than others, these decisions should not result in the exclusion of other groups. This is why public institutions need to take a critical look when adopting private sector design practices, like audience segmentation and profiling.

In Conclusion

I will elaborate on these six principles and giving concrete examples on my posts and talks in the coming months.

As a concluding note, my approach to convivencia focuses on learning and action in a world that is real, wonderful and slightly broken. It ties my approach to theories that emphasize democracy as an active state of learning (Arendt 2002, Dewey 2006).

The emphasis on skills and capabilities builds on the work of development theorists like Amartya Sen (Sen 1999) and Martha Nussbaum (Nussbaum 2011. They concluded based on research on women and the poor in India that rights are largely worthless if people do not have the institutional support, societal norms and the individual capacities to exercise them and if people do not have the agency to make choices. Nussbaum, in an Aristotelian tradition, has challenged narrow ideas of what constitutes good life by emphasizing the role of play, rest and the humanities (Nussbaum 2011; Nussbaum 2017). This makes her work highly relevant to cultural and heritage institutions, like libraries and museums.

I have intentionally emphasized friction in convivencia to highlight the need for diversity and equity. Based on my leadership experience in public spaces and work in demanding professional settings as an openly gay man, I see the recognition of friction as a prerequisite for equity. It allows us all to join the party.

As a former senior executive of a large public service delivery organization, I refrain from pure celebration of conflict typical in some urban policy debates. I intentionally talk about friction instead of conflict.

It is also worth noting that what convivencia looks like and feels like is contextual and situational. Convivencia in Northern Canada might look different than in the Mediterranean. And the space that was welcoming and inspiring yesterday, might be intimidating today due to what happens in society or the lives of the particular people in the particular space in that particular moment.

I suggest convivencia as an actively nurtured space between harmony and open conflict. This is to say that there is a level of friction that is ideal for innovation and service delivery. At times, it requires highlighting differences and at other times you need to bring the temperature down through mediation and reconciliation. But simultaneously, this means that public space organizations do not have the luxury for endless analysis and dialogue. After a well structured dialogue, they have to be able to take action. They have to open their doors every day and get things done.

(This article has benefited from research conducted during my 2022-24 fellowship at the Bloomberg Center for Public Innovation at Johns Hopkins University.)