On Power

It's OK to want to have power. Relational power requires different leadership skills than unidirectional authoritarianism.

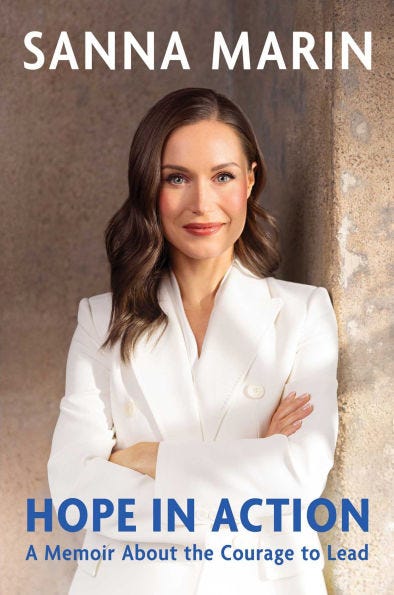

Over the last couple of weeks, the Finnish media has been obsessed with former Sanna Marin who recently published a book on her time as the youngest Prime Minister in the world.

As Prime Minister, Marin became an overnight political superstar in the same league as Canada’s Justin Trudeau, New Zealand’s Jacinda Ardern and most recently the first openly gay Prime Minister of the Netherlands, Rob Jetten.

Most of the stories on Marin focused on her gender, her age and the fact that she was leading a five-party coalition government where all the parties were led by (mostly young) women (see HBO documentary trailer below).

We Finns always have mixed emotions when one of us becomes famous. While we feel a sense of pride (Finland in the news!), we remain alert for any signs of arrogance or condescension (as in ”does she think she is better than the rest of us”). Sadly, this scrutiny is tougher for young people and for women, especially tough if you happen to be both.

A lot of the stories on Marin in Finnish media have been somewhat critical. Her book has been criticized for being rushed, categorized as capitalization of her political career or, God forbid, “very American”. (Full disclosure: I have not read the book.)

On November 7, Finland’s largest newspaper Helsingin Sanomat featured Marin on her book tour in New York. In an expected fashion, the journalist made snarky comments about the audience not really knowing who Marin was and her doing the talk in the small and wealthy small town of Chappaqua (the home town of Bill and Hillary Clinton).

But the most fascinating part of the article was a quote from Marin. She was asked what she missed from her time in politics. She responded:

”But what do I miss?

Actually I miss the most power.

That’s why I went to politics in the first place.

I love, I loved making decisions. I loved making decisions.

I love power where you can really influence things. ”

former Prime Minister Sanna Marin

(you can watch the exchange between Marin and Huma Abedin on the video below)

Lean into Power

I love Marin’s response. It is not something you hear very often. Most candidates and politicians talk about their work through a calling or a sense of duty. But Marin makes an important point: having power allows you to turn your calling into action.

I am in no way comparing myself to Marin. I am not a political superstar, don’t have a six-figure book deal and have not been featured in an HBO documentary. But I have held institutional power in my roles with the City of Helsinki. And a lot of my current work is with mayors and other city leaders who hold substantial amounts of power.

My advice to leaders comes across at times as counter intuitive and surprising. I encourage leaders to lean into power. I think the best way to build trust is to talk about power openly and to use it based on open and public deliberation.

As a political scientist, I see power as neutral. Moral judgement on power should only be exercised after reviewing what that power is used for. Some people having power and using it is not a bad thing if there are functioning accountability and transparency mechanisms. That is the difference between good governance and autocracy.

I often witness how non-leaders are frustrated by their superiors who hide their power by using it in secret, who do not justify their decisions, who do not tolerate critique, who retribute and hold grudges, or who mask their power in language of collaboration (“we decided”) or abstraction (“it was decided”).

I also see a lot of leaders who confuse dialogue with power. As Alhanen, Soini and Kangas write in their brilliant essay on dialogue and power, dialogue is a way to gain understanding on an issue while it is often a poor mechanism for making decisions. They write:

It is important to separate dialogue from decision-making, and it is good for the leader to understand that not all work meetings and not all issues are suitable to be processed through dialogue. Dialogue requires well-developed mutual equality and a momentary suspension from driving one’s own interests. These factors are different in decision-making. The leader’s inequality as a user of power is emphasized and employees strive to achieve of their own interests.

For civil servants and elected leaders, power is coupled with responsibility and, ultimately, liability. Your actual job is to make decisions. While it is wise to gather insights and consult executive leadership teams and seek for shared understanding, my decades of city leadership and consultancy have convinced me that most people appreciate when you make it clear that you are the one making the decision. That you are the one holding power while understanding that the power you possess is always on loan and linked to your institutional role, not you as a person.

Peculiarities of Cultural Leadership

I have been thinking about power and leadership a lot lately in my work with the World Cities Culture Forum (WCCF), the leading global network of city leaders in the arts from over 45 cities representing all continents and a total population of 245 million (highly recommend their new World Cities Culture Report on the state of the arts in 45 big cities) .

Despite culture’s critical role and the demands of leadership roles, the network has recognized that there is no formal training or route for future culture city leaders. Whether they are elected officials, mayoral appointments or career civil servants, they all work at the cross section of municipal power, politics and the arts. As a result, WCCF is exploring the need for a fellowship program tailored for senior cultural leaders in cities and they asked me to help in developing the format based on consultations with universities, member cities and other potential partners.

The annual summit of the World Cities Culture Summit in Amsterdam in October was an opportunity for me to develop the proposal with leaders from around the world. Based on my own experience from Helsinki and the consultations in Amsterdam, it is clear that power in the field of arts and culture plays out in a somewhat peculiar manner. Very few cultural leaders have the kind of substantial regulatory powers like their colleagues in social and health, education and urban planning. The roles vary greatly in terms of resources with some overseeing large direct service delivery arts institutions while others having mostly grant making and policy tools. As you work with questions of memory, identity and belonging, you are dealing with an extraordinary emotional load.

I love this assignment. Art and politics by definition challenge each other. The work of the municipal leaders is ultimately about navigating friction rather than solving it. Zadie Smith captures this dynamic well in her new essay collection Dead and Alive:

“Power dominates, but art proliferates - and not always along the lines that power dictates. For art, unlike power, can never be wholly unidirectional, artists themselves being at once too voracious and impure in their methods. Whether members of dominant or subjected communities, they will prove capable of appropriation, hybridization, adaptation. To put it another way, while the master isn’t looking, many interesting things will be made with his tools.”

Relational Power

When developing the fellowship program, I find myself going back to a basic typology of power.

Power over: having influence and control over others, mostly without the requirement for consultation.

Power to: having the ability and authority to effect or achieve outcomes, either independently or collaboratively.

Power with: having the skills and ability to effect things through learning, advocacy and collaboration, with a focus on cooperation over coercion.

While there are exceptions, most roles in cultural leadership rely on relational power, i.e. some extent of power to and mostly power with. The biggest accomplishments for arts and culture do not usually come from growing the cultural budget but from integrating arts and culture into other policy areas, like public art in public buildings, creative aging in senior care, ensuring event facilities on streets and public squares, faster permitting, recognizing the arts as a driver for events and tourism, or the utilization of “difficult” public assets, like protected or vacant buildings, for cultural use.

Relational power (power to, power with) requires different skills than unitarian domination (power over). Relational power requires curiosity and empathy to ensure you create spaces where people feel comfortable to be authentic with you on the resources at their disposal and their possible concerns and reservations. Relational power requires creating processes where people are willing to adjust their own approach to meet some shared and common good. It is being comfortable that we might not all be in this for the same reason while we need each other to make some great things happen.

10 Principles on Relational Power

Here are ten relational power principles I have found working well in public institutions, especially in the fields of culture and leisure:

When you convene people, be clear on the intent of this gathering: is this meeting for development (dialogue) or for decision making?

Make power and power differences visible while not belittling people. Make sure everyone understands who makes the decision.

While gathering data and understanding your options, ensure you understand the goals and motivations by others, often by repeating back to people what you have heard and inviting them to add or correct.

Good dialogue has a beginning and an end. Be clear when you have sufficient understanding to make a decision and when you are moving from dialogue to decision making.

In most cases, I would not encourage seeking compromise. Too often the cost of compromise is lowering ambitions and losing focus. I like Carlos Lozada’s idea of a 73 percent agreement where “you’re largely on my side, but there’s still room for debate”. Seek for a pragmatic yet ambitious way forward, which everyone can stand behind rather than a trying to build a 100% fan base for your chosen approach.

Uphold highest standards for transparency. Present the counter arguments with the same care as you would present those supporting your position. This is especially the case when you as a civil servant or a political leader prepare a proposal, like a budget, to a political body.

Be explicit on the decision that you take and when you take it. Communicate it both verbally and in writing. Offer room for questions and clarifications. Dare to use ‘I’ language when you are the one holding the decision making authority.

When the decision has been executed, choose your strategy based on perceived success. When things go well, share glory with partners and your team. Share feedback and praise you get from stakeholders and city leadership with your team. But when things go haywire, protect your team and partners and emphasize your role as the decision maker. When the dust has settled, focus on your reflection on what you can learn from all of this.

Build accountability mechanisms for yourself to remind you regularly that your power is always on loan and it is linked to the role rather than you as a person. Many leaders are quite surprised how interactions with stakeholders change when they no longer hold power.

Solicit regular feedback. Collect feedback on your leadership from your direct reports and their direct reports. Use an external consultant or your HR team to summarize the feedback and lead a dialogue with your team around it. Communicate to people what you learned from the feedback. Share the summary with your boss.