Investing in Los Angeles

LA is the only big US city without a capital plan. Mayor Karen Bass is set to correct that. Jessica Meaney from Investing in Place explains why this is needed.

A few weeks back, I got a call from my incredible friend Sandra Kulli (who was also the first supporter of this Substack). Sandra is this gentle powerhuman with never ending, yet critical kindness. She is dedicated to connecting people to people. She has been instrumental in broadening my professional connections here in Los Angeles. When Sandra calls, I always answer. She usually has exciting ideas.

Sandra is a member of the Downtown Breakfast Club, which convenes designers, developers and civic actors committed to the development of Downtown Los Angeles. The club was hosting a session at the California Club on the opportunity presented by the 2028 Olympics. She asked if I would like to join. I said yes.

One of the speakers was Jessica Meaney, the Founder of Investing in Place. She has committed her career to pushing for systemic changes in how the City of Los Angeles plans and budgets investments. According to Jessica, Los Angeles is the only big US city without a capital investment plan. This might sound like just another government document but it is not. Capital planning and investments are really about whether and when your sidewalk or your street lamp gets fixed or not (some research on LA’s backlog here).

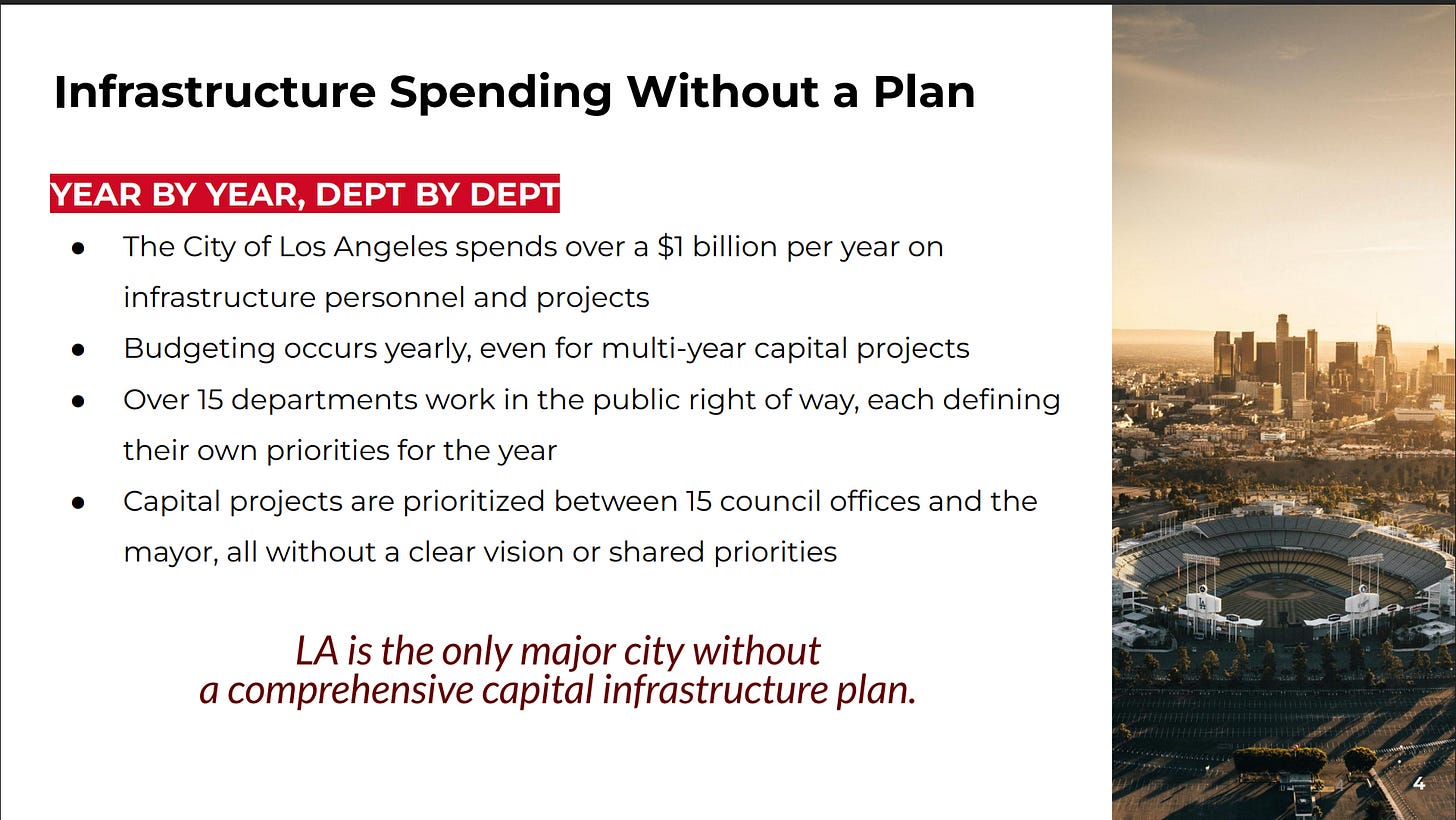

The only major US city without a capital infrastructure program

Digging into the issue and reaching out to the city, I was delighted to learn that Mayor Karen Bass has gotten the wheel rolling on this. Based on a presentation given to the Pedestrian Advisory Committee last March, the city shares the urgency of the matter.

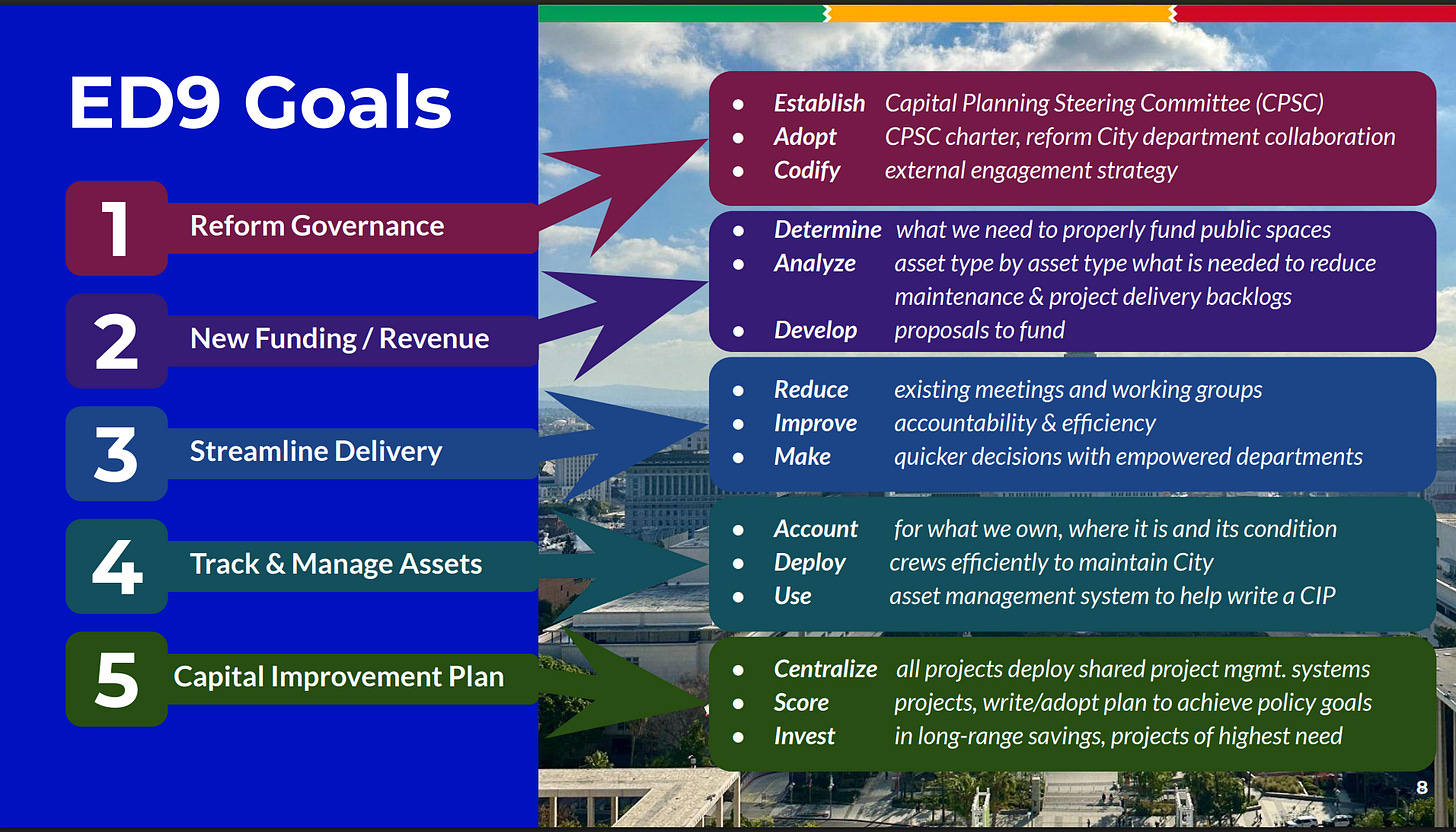

In October last year, Mayor Bass introduced the Executive Directive 9 laying out the ambition for a capital investment committee, creating a governance system, developing a financing plan with new revenue models, consolidating existing committees, introducing centralized asset management and introducing strategic, long-term priorities. The progress of this work can be followed on the city’s public website.

While starting the planning is great, one should not underestimate the complexity of this task. I reached out to Jessica to learn more about why this matters and what all of us Angelenos could do to fix this systemic problem.

(The conversation below is edited for clarity and length.)

“It's lots of cooks in the kitchen, but lots of cooks in the kitchen using their own recipes.”

Tommi Laitio: First of all, thank you so much for taking time to talk to me. Let’s start from the basics. What is Investing in Place?

Jessica Meaney: Investing in Place is a nonprofit I started about 10 years ago focused on leveraging public space to improve quality of life. We look at how public dollars are spent. Who decides? Who benefits? Where do they go? What are the processes behind that?

Tommi Laitio: I've been living in Los Angeles for one and a half years. When I moved here, I read this book by Rosecrans Baldwin called Everything Now: Lessons from the City-State of Los Angeles. He writes: “Los Angeles probably has no single, unifying dream besides the straightforward desire to be loved and not to die in an earthquake. Or perhaps not to feel so alone in the vastness of the immense slouching shapelessness of it all.” What does place mean in a megacity like Los Angeles?

Jessica Meaney: It's all the wonderful 200+ neighborhoods and the people who make up those communities. I moved to LA in the late 90’s. I’m not someone who really likes to drive, I tend to walk, ride the bus or my bike to get around. So for me, public space is where I see my neighbors, the fruit vendor Gilberto, my mother-in-law on her way to the bus to head downtown.

Even though LA has really been going through a tough time, particularly this year, the culture and the people are why we are all here. Public space for me also has been transit and the calmness and the independence I've felt over the years when I get on the bus and can control where I'm going. I can people watch. I can even eavesdrop. I can see teenagers having a good time with nobody watching. That element of public space is what I continue to get drawn back to. It’s what you read: not to be alone and to be together, with a wonderful sense of independence.

Tommi Laitio: Often when you work with public spaces, you are in this discussion about system-level change and bottom-up placemaking. Where's your focus on that?

Jessica Meaney: Systems change. I'm really interested in a city-wide management of public spaces. I got to this point over 10 or 15 years of working in nonprofits. Like what does it take to get better bus shelters? What does it take to understand how the sidewalks are invested in? It was like whack-a-mole. You try to work on one issue and then it pops up in another place. People constantly saying that there's no money for this or that. It led me to ask where the money is going and who is deciding.

Several years ago, we were working on elevating perspectives of immigrant mothers and their transportation needs with several partner organizations. We sent a letter to the mayor of Los Angeles and four general managers saying: can you help us understand where the dollars are going? And nobody could. It was unearthing that there was no plan. People were putting their finger on the dam for each specific issue. So when you request an access ramp for a sidewalk, you're gonna wait 10 years. It's a year to get a street light fixed. There's 200,000 empty tree wells. There's 8000 bus stops but maybe 2500 of them have shade. There's 14 public bathrooms for a city of 4 million, and I’m pretty sure several of them are closed right now.

And during all this work, I’ve continued to go back to this impressive, well researched report the city put out in 2017, that has inspired so much of my work, saying that LA is the only major city without a capital infrastructure program. Nobody really knows where the money is going. So everyone's in the dark: the policymakers, the community members, the city staff. At the heart of that is sharing power in understanding the state of what the city's public spaces are. The city is 500 square miles.

If you don't know what your infrastructure is, and you don't know what condition it is in, I don't know how you prioritize, maintain or build new stuff. Public spaces would be greatly improved if there was just a maintenance program, if LA had a trash pickup program that was funded to meet real demand, if trees were maintained, if the parks were adequately funded and operated. What I think is really hard with the City of Los Angeles is that they budget one year at a time and are mashing up capital and operating dollars.

Tommi Laitio: It basically means that you don't really have a balance sheet because you don't know what the assets are, right?

Jessica Meaney: Yes. At least 20 different departments are working in the city's public right-of-way, all with different budgets and different project lists. It's lots of cooks in the kitchen, but lots of cooks in the kitchen using their own recipes. There's such brilliant staff working for the city but without a unified work plan, everybody's just digging in and trying to make their own difference. And then layer on top of that the issues of power and access.

I think a lot about the question: what do we expect from government? Is it understandable for an Angeleno to want their street lights to work? To have your 311 request for an access ramp (curb cut) actually result in one in a timely manner? Is it reasonable to want shade when they walk to the store? I think so. I would be remiss too not to mention the incredible housing challenge the city is having and the incredible humanitarian crisis of 40,000 people living on the streets in LA. And layer on top of that all of our beautiful street vendors who are literally supporting their families by selling us those delicious bacon-wrapped hot dogs.

Need for Community Support for Systems Change

Tommi Laitio: So what’s your theory of change, in terms of how you could get to that? No one's gonna win elections by talking about a capital investment plan. So how do you think a city like Los Angeles gets to having a capital investment plan?

Jessica Meaney: I don't think you can sell, necessarily, a politician to run on the campaign on the capital infrastructure program. But I certainly think you can sell policymakers and politicians and elected officials to run on campaigns of a well-run city, a city that works for Angelenos. For someone who says, I'm going to get the street lights fixed, I'm going to get your 311 request, and so really fix the management and the delivery of tax dollars so community members can see the benefit of that. How we get to that point, involves culture and civic leadership and community and the realization of. I think there's so many brilliant people here in Los Angeles that are maybe focused on so many other things, but haven't had the opportunity to understand the brokenness of the current system and the opportunity to fix it. I also think there's brilliant people like you and other cities who offer solutions forward, who offer best practices of how to involve philanthropy, how to involve civic leadership, how to involve artists, how to involve youth. Angelenos deserve it. We can do it.

Tommi Laitio: You make me think of the work of Jen Pahlka. This idea that we can be in favor of government, but for better government. Being in favor of government doesn't mean that you support everything that the government does at the moment. What moved me and resonated with me, when we talked last time, was your call to civic leaders and business leaders, that we need advocacy for these changes. We can't just expect our political leaders or department heads to take care of this. If I think of the research I did on the Rebuild program to renovate parks and libraries in Philadelphia, the really critical part of that was mobilizing Friends of the Parks and philanthropic support.

Jessica Meaney: Yeah, I think that's where I'm landing. After about 15 years of this work, we struggle on implementation and power if there's not a diverse set of players, actors, voices, perspectives behind it. It seems like in well-run public spaces and cities there is a strong component of philanthropy and community members. In Minneapolis, they have a whole advisory committee for their capital infrastructure program. It's based on a lottery. So it's not just people who have spare time and who are in the know who show up, but making an effort to have citizen advisory community members and advisory committees reflect the demographics that lives in that city. And at the same time leaning into influential people who can elevate these conversations and resource these conversations. I think that's long overdue for LA.

Tommi Laitio: This was exactly the research that I've been doing over the last couple of years. How do we build partnerships where we recognize that we are not all having exactly the same goals, but there's enough alignment for us to push for certain things? I just published this paper on Charlotte and Mecklenburg County, where philanthropy really works as a broker of coalitions. What I have found is that solid coalition building requires understanding that if you're a neighborhood organization, your perspective on the needs are probably different than that of a real estate developer or a big local business. But there's enough alignment, enough shared agenda to really push for change. In this case, we could all rally around the need for a capital plan while having very different views on what goes into that plan. My whole work has been to build these kinds of coalitions to recognize we need to validate those differences. But if there's no codified plan, it's like trying to play a board game together without rules.

Jessica Meaney: I think that's what's happening right now. There are rules, but they're very quietly spoken in certain rooms. I also say that there are a lot of brilliant people in the City of Los Angeles who are tapped out for good reason. So I've been thinking about the future. How do we create more spaces to be in conversation with each other, with an attitude that we can take care of each other?

Tommi Laitio: I really appreciate you saying that. Coming from the government myself, and also working with civil servants, most people who work in these systems want better systems. They are not your enemy. 90% of the civil servants that I've encountered in my career are very dedicated. They love their city. They love the work they do. They're not actively trying to delay things or cause harm to residents. They're just working in legacy systems and dysfunctional systems, trying to keep it going.

An Opportunity Presented by the Olympics

Los Angeles is about to host the Olympics and the World Cup. What is the opportunity for pushing this work forward that is presented by these big events?

Jessica Meaney: I think it's an opportunity to dig deep and not only create a vision for the future of the city, but to get to work together making it happen. It's an opportunity to realize the need for leadership and collective power around our public spaces. I think it's a little bumpy. I think LA is a little bit behind in planning for these events, but I think it's going to be okay. I'm around a lot of very concerned people, but I think there's a lot of smart people doing the best they can with what they have. If civic leaders and others come to figure things out together, it can be a turning point.

Tommi Laitio: I love that you say that. I’m from a smaller city [Helsinki], but my experience from events is that if you frame them as a way to improve the lives of residents and create connections between your temporary residents (tourists) and your permanent residents. If you think of visitors coming that they would be temporary residents in your city, you want them to have an LA experience. I've seen in Helsinki, being a World Design Capital in 2012 changed the way we engage residents in human-centered design. Or how being the European Capital of Culture meant that we learned how to open public spaces for use by easing our permitting. I've seen this in so many cities that you frame the events as a way to improve your city for your residents rather than as dealing with this flood of outsiders. That needs to happen also to have the legitimacy of hosting these events.

Jessica Meaney: Yeah. Instead of denying and acting like everything's gonna be great, can it be okay to talk about the inequities, the challenges, the broken systems, and still host with an open heart and a kindness and a focus on creating public spaces. I really hope for the World Cup that for instance when Guatemala plays, all the Guatemalans can get together and we can celebrate being together and be honest. Yeah, things aren’t really perfect, but we're still here. We're still committed to making it better and we're still committed to being with each other. We're doing the best we can and we just want to be together.

That sounds like my family's Thanksgiving. Of course we need to make sure that there’s enough adequate transportation, shade and public bathrooms, all of that. But then re-centering over this idea of celebrating human human spirit.

Tommi Laitio: It's funny that you use the Thanksgiving example. When I talk about the idea of convivencia, Thanksgiving is the example I usually use for North Americans. There’s love and affection and joy, but it also takes quite a lot of effort to not jump on every possible disagreement. And to make room for people who are slightly different than you, and have the benefit of the doubt in a lot of situations. That is convivencia.

Thank you so much for taking the time to chat with me.